Welcome back you amazing nerds. In this text I plan to continue exploring Plato’s theory of ideas and pick up at the cliffhanger I left you in the last text. Today we’ll be exploring one of the most well-known metaphors of Plato: the allegory of the cave (Russell, 1946).

But how do we get into this cave? In the last text, we learned how Plato compared sight to knowledge, with sight being the power for visible things, and knowledge being the power for things that are (Adamson, 2014; Kenny, 2010). For sight we use our eyes to see things that are illuminated by the light of the sun, struggling to see things when the sun is down and there is darkness. In a similar way, we use our soul to understand what things are real when they are made perceptible by the truth coming from the Idea of Good (Adamson, 2014).

Thus, the philosopher’s quest for knowledge will be similar to one moving from the darkness of belief, where they have difficulty seeing the world as it really is, to the light of truth projected by the Idea of Good, thus being able to see the Ideas and, therefore, the real version of the world. It is this journey that Plato presents through the allegory of the cave.

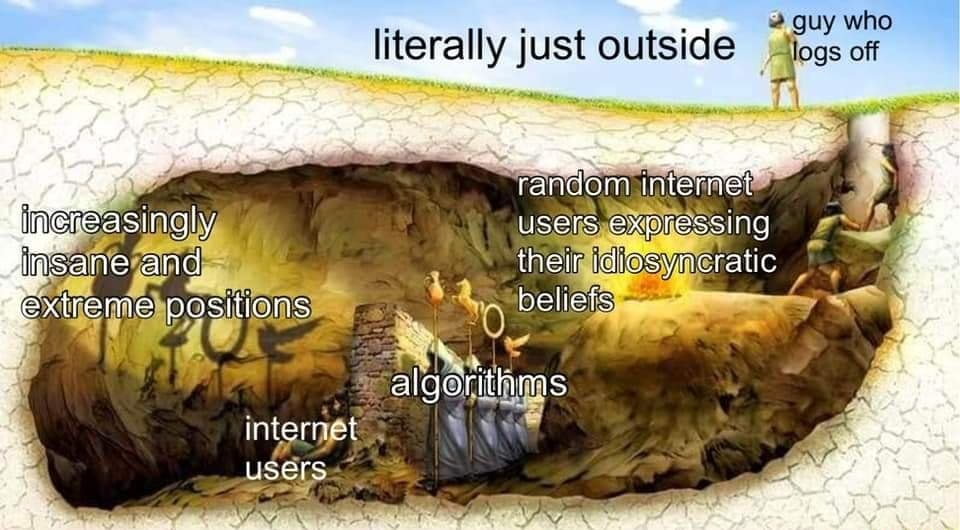

Imagine then a group of prisoners chained in the depths of a cave. Because they are chained, they are only able to look to the deepest wall of the cave. Behind and above these prisoners there is a wall, behind which there is a fire. Because of this fire, most of the time all the prisoners see are the projected shadows of themselves. Behind the wall, there are also other people who are carrying statues of different objects and beings, which also have their shadows projected into the wall. Because the prisoners can only face one way and all they see are these shadows of themselves and of the statues being moved in front of the fire, they are detached from reality, thinking the shadows are real, having no awareness that they are just shadows cast by fire of things that are also not real themselves, the statues. Because all they know are shadows, the prisoners spend their days trying to identify shadows and predict which ones will be coming next. These conversations and games are pointless, as they keep the prisoners in their ignorance from reality and don’t benefit them in any way. However, the prisoners are very passionate and serious about it. Again, all they know are these shadows (Adamson, 2014; Russell, 1946).

Now imagine one of the prisoners manages to become free from their chains. They would be able to move around and for the first time see the statues and the fire. Initially this would be a scary and uncomfortable experience, as it would challenge their familiar understanding of all there is to the world being the shadows, and due to their eyes not being used to the light of the fire. If they kept going past the fire, they would eventually see gradually more and more brightness coming from the entrance of the cave. This would be a difficult journey, as the light would initially be blinding, so the prisoner would have to give their eyes time to adjust, and their body would quickly get tired from the climb up from how long they have been shackled without moving. If, however, they persevere through this difficulty, they will eventually get out of the cave, into the real world outside, seeing all the things that exist in it illuminated by the light of the sun (Adamson, 2014; Russell, 1946).

At this stage the prisoner would understand that this is reality and that so far in his life he had been tricked by unreal things projected from imperfect copies of objects and beings. Following a likely existential crisis, the prisoner might feel a duty to tell the truth or even try to free his fellow prisoners. If the prisoner does try to do this, they will however struggle, as after being in the outside, under the sunlight, their eyes will struggle to see in the darkness again, causing them stumble and struggle to find their way back down. When he gets to the other prisoners, they will likely not believe the free prisoner, as now the later looks somewhat stupid stumbling around the cave, and all the prisoners know is shadows in the darkness, having no concept of the outside world of the light of the sun (Russell, 1946).

This allegory aims at illustrating that most of us start in a state of ignorance, not being able to see the world as it really is. Just like the prisoners engage in conservations about shadows, we also spend time talking about the lives of celebrities, the brands we like, the latest fast-food chain restaurant that opened in town, or the latest tik-tok meme trend (Adamson, 2014). These things are all distractions we created ourselves and that aren’t really useful for us in life, nor contribute to our well-being. They don’t help us understand the world or ourselves better, but still, we seek them daily. The same way the chained prisoners struggle to believe and understand anything beyond shadows, so do we become uncomfortable when we face facts or ideas that challenge our current biases and world views, possibly feeling defensive against people who do so. On the other hand, the freed prisoner will struggle to return back down the cave and will not have interest in the conversations about shadows, paralleling how a philosopher will struggle to engage with the day-to-day superficial conversations after obtaining knowledge, sometimes struggled to identify with society in general (Adamson, 2014).

Adamson (2014) also argues that, despite the allegory of the cave being part of most “introduction to philosophy” courses, two misconceptions are often made. First is that by presenting the world of Ideas as the “truer” reality outside the cave, and our general reality as the “less true” reality inside the darkness of the cave, Plato is describing there existing two separate worlds. However, these worlds will be connected, as similarly to how a prisoner can unchain themselves and get out of the cave to see the real world, so can philosophers grasp a more real version of the world through knowledge. The shadows on the cave wall are still in the shape of the real objects or beings outside of the cave, making the two worlds connected. Instead of the existence of two worlds, Plato can be said to be trying to illustrate a distinction between belief and knowledge: how our understanding of reality can change depending on if we look at it based in our poorly formed and incomplete beliefs, or through more rigorous and critically obtained knowledge.

The other misconception that can be made about the allegory of the cave is that Plato is describing and supernatural and mystical experience where one would gain otherworldly knowledge that cannot be explained to other people through words, by means of a flash of insight when leaving the cave (Adamson, 2014). However, Plato describes the journey out of the cave as effortful and requiring the prisoner to allow time for their eyes to adjust just to get to the border with the outside world at the entrance of the cave. This parallels the laborious process that is reading, studying and reflecting one goes through when trying to learn something. This analytical and active process is what lets us obtain structured knowledge in such a way that first principles are ascertained and serve as a logical and factual base for other truths about reality (Adamson, 2014). This process is linked to what Plato calls “Dialectic: a complex analytical process where hypotheses are made and tested, often by other people. Thus, the freed prisoner can’t convince the chained prisoners about the reality of the outside world not because this knowledge is to mystical to be put into words, but because the chained prisoners would also have to adhere to the process of dialectic in order to understand (Adamson, 2024). An example would be trying to convince someone who is anti-vaccines that these are safe and well-tested without them believing on or understanding peer-reviewed controlled clinical trials. If an anti-vaccine person thinks their beliefs are the only thing that counts to understand the world, no number of facts presented is likely to change that.

I hope that this text has made you reflect on how your beliefs and pieces of knowledge can change how you understand and view the world. You might think that you are knowledgeable and there is nothing wrong with your world view. And I’m not writing to say otherwise. However, keep in mind that the prisoners in the cave didn’t question themselves about the existence of a real outside world. How could they, if they weren’t aware of it? They lived their life in darkness and all they knew were shadows.

Despite inspiring movies, the idea of a supreme God in an otherworldly heaven, and other philosophers throughout the ages, Plato’s theory of Ideas and allegory of the cave aren’t without flaws. Some of them you might have picked up on already. They certainly have been noticed by other philosophers since, and even Plato himself pointed some flaws in his doctrine, as a proper philosopher should. I will be analysing these shortcomings in the next text.

I hope to see you amazing nerds there. Be critical about what you think,

The Physiolosopher

References:

Adamson, P. 2014. Classical Philosophy: A history of philosophy without any gaps, Volume 1. 1st edition. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Kenny, A. 2010. A New History of Western Philosophy: In Four Parts. Reprint Edition. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Russell, B. 1946. History of Western Philosophy. Routledge – Taylor and Francis Group: New York.