Hello again amazing nerds. In a previous text I went through how pain is a complex and biopsychosocial experience. But for some of you, the question may have remained: what is actually happening in our body when we feel pain? How does that experience emerge in our body and what role does our anatomy and physiology play in it? That is going to be the topic of the next two texts.

For us to make sense of this process, we need to start by talking about Nociception. This term has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as the “neural process of encoding noxious stimuli” (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019; Hudspith, 2022; Internation Association for the Study of Pain, 2011).

The term “noxious” means something that is or can potentially be damaging to the tissues in our body (Hudspith, 2019).

So nociception is all about our body translating things that can be threatening to it so the brain can make sense of it and decide what to do. This happens through nociceptors, primary sensory neurons which have specialised channels at their ends that allows our body to turn threatening (noxious) stimuli into electrophysiological nerve signals (action potentials) – a process known as Transduction – that are sent to the brain (Gooding and McMahon, 2021; Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019).

There exist three main types of noxious stimuli: thermal, chemical and mechanical (Hudspith, 2019).

Thermal nociception is what allows us to perceive temperatures that are so hot and so cold to the point they could cause damage to our body, thus prompting us to avoid the sources of such temperatures. This is mediated through capsaicin (the active substance in chili peppers) sensitive TRPV1 vanilloid channels for heat and menthol-sensitive (TRPM8) receptors for cold (Hudspith, 2019). These receptors are the reason why when we eat pepper or chilies, it feels like our mouth is burning, and when we eat a mint our mouth feels cool.

Chemical nociception is how our body identifies changes in the levels of chemicals inside of it, for example when we don’t have enough blood flow to a part of our body (ischemia), when there is inflammation in a part of our body, or when an external chemical irritant agent gets inside our body in some way (Hudspith, 2019).

Mechanical nociception is mediated by cell-membrane deformation that allows us to perceive forces causing compression or tension in our body. We still don’t fully know the receptors involved in this process, but there appears to be some overlap with thermoreceptors and chemoreceptors (Hudspith, 2019).

The receptors for these different kinds of noxious stimuli are found in specific afferent (conducts from outside to inside) nerve cells of small caliber, which are named nociceptors. These are divided into Aδ-fibres and C-fibres (Goodwin and McMahon, 2021).

Aδ nociceptors are myelinated fibres, appear to transmit mainly thermal and mechanical nociception, often leading to what is known as first pain sensation – well localised pain associated with acute injury (Hudspith, 2019). As mentioned above, nociceptors appear to have a mixed or shared role in mechanical nociception. Aδ nociceptors in particular, are deemed high-threshold mechanoreceptors and may be categorized according to their stimulation threshold (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019):

- Type I High Intensity Mechanoreceptors (HTM) are activated by heat (>50ºC) and noxious mechanical stimuli. Type I HTM are usually responsible for the immediate pain we feel with something like a pinprick.

- Type II HTM have a significantly lower thermal threshold (45ºC heat) but a much higher mechanical threshold. Thus, they underlie the pain we immediately feel when we touch something very hot.

C-fiber nociceptors are smaller, unmyelinated fibers, that can also be divided into high-threshold and low-threshold (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019). They are described as transmitting what is known as second pain sensation – a more diffuse and dull type of pain (Hudspith, 2019).

High-threshold C-fibers are the actual nociceptors, responding to thermal (> 45ºC), noxious mechanical, and noxious chemical stimuli, while low-threshold C-fibers respond only to non-nociceptive stimuli (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019).

Despite their different characteristics, both of these nerve cells will have their cell body at and connect to a part on the back of our spinal cord called the dorsal horn, where they synapse (connect) with second-order afferent neurons that take the information to our brain through what are called ascending pathways (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2019; Hudspith, 2022).

Before we carry on, just a quick recap:

- We have these specialised nerve cells with specific receptors for things that are potentially dangerous to our bodies.

- Potential dangers to our body are divided into thermal, mechanical, and chemical, and they only become dangerous, thus activating these specialised receptors, when they reach a certain threshold.

- When that threshold is reached, these nerve cells turn these potential dangers into nerve signals which are sent to the spinal cord, to travel up to the brain.

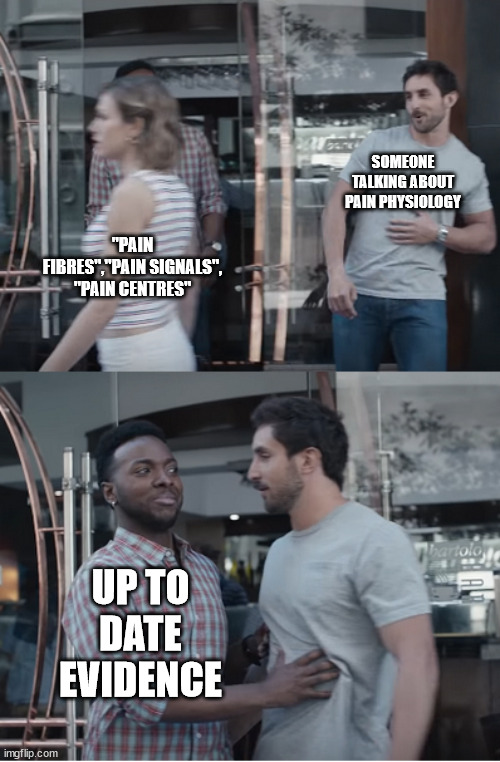

With me so far? Good. Some of by now may be thinking that basically what we are talking about are the pain fibers or nerves in our body that send pain signals to the pain center in our brain. In case this is happening, I have to stop you here.

It is important to note that all the research we have so far points to the fact that pain is different from nociception (Raja et al, 2020). In the different physiological steps that I’ve described so far, our body is not experiencing pain and it may not end up experiencing pain just because the nociceptors have been activated.

From this, I can also point to the fact that there doesn’t exist a thing such as ‘pain nerves/fibers’. What we have are receptors for thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimuli that may or may not have the potential to damage our body. For those to become painful, they will then have to be sent to the brain where they are processed but not by a pain center, because this doesn’t exist (Gore, 2022; Hudspith 2019; Hudspith, 2022), but by different areas and cortices of our brain that communicate together (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2022).

These brain areas include the somatosensory cortex (area associated with sensory discrimination), anterior cingulate cortex and insular cortex (areas involved in emotion), amygdala, and limbic structures (areas involved in fear and anxiety), among others (Hudspith, 2019; Hudspith, 2022).

These separate brain areas have been shown to have patterns of synchronous activity (Gore, 2022; Hudspith, 2022). Based on the available evidence, it is theorised that this linked activity is what creates the representation of our Self with its different parts, including multidimensional bodily states (Hudspith, 2022). When this network judges that the information received from the nociceptors will threaten the homeostasis of the body and Self (independently from if it actually does) it will create the experience of pain to prompt us to act and preserve our homeostasis and the Self (Hudspith, 2022). But this network of brain areas is also involved in other non-noxious activity, so at other times, despite the nociceptive inputs being present, they are not considered a threat and the pain experience is not felt (Hudspith, 2022).

But how does the brain and rest of the nervous system control the response to threat? Shouldn’t it always respond with pain if nociceptors are activated? Why can our pain experience be so varied, with some of us experiencing more, and others less, pain?

Because this text is already getting long, I’ll explore that in a second text on Nociception.

I hope to see you on the next one,

The Physiolosopher.

References:

Goodwin, G., & McMahon, S. B. (2021). The physiological function of different voltage-gated sodium channels in pain. In Nature Reviews Neuroscience (Vol. 22, Issue 5, pp. 263–274). Nature Research. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-021-00444-w

Gore, D. G. (2022). The anatomy of pain. In Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (Vol. 23, Issue 7, pp. 355–359). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2022.04.002

Hudspith, M. J. (2019). Anatomy, physiology and pharmacology of pain. In Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (Vol. 20, Issue 8, pp. 419–425). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2019.05.008

Hudspith, M. (2022). The genesis of pain. In Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (Vol. 23, Issue 7, pp. 360–364). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2022.03.007

International Association for the Study of Pain. (2011). Terminology | International Association for the Study of Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., Cohen, M., Finnerup, N. B., Flor, H., Gibson, S., Keefe, F. J., Mogil, J. S., Ringkamp, M., Sluka, K. A., Song, X. J., Stevens, B., Sullivan, M. D., Tutelman, P. R., Ushida, T., & Vader, K. (2020). The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. In Pain (Vol. 161, Issue 9, pp. 1976–1982). NLM (Medline). https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939

One thought on “Nociception part 1: How do we know when to hurt?”